“You have two eyes, two ears, but only one mouth. You should use them accordingly.”

“The Culture Map” by Erin Meyer provides a framework to understand the most common business communications challenges that are present when you are working in a global context, with colleagues or stakeholders from different cultures.

By assuming that culture does not matter, our default mechanism will be to view others through our own cultural lens and to judge or misjudge them accordingly.

To be successful in a cross-geo context we need to have an appreciation for cultural differences as well as respect for individual differences because both are essential. Cultural patterns of behavior and belief frequently impact our perceptions (what we see), cognitions (what we think), and actions (what we do).

The book contains eight scales that map the world’s cultures:

- Communicating: low-context vs high-context

- Evaluating: direct negative feedback vs indirect negative feedback

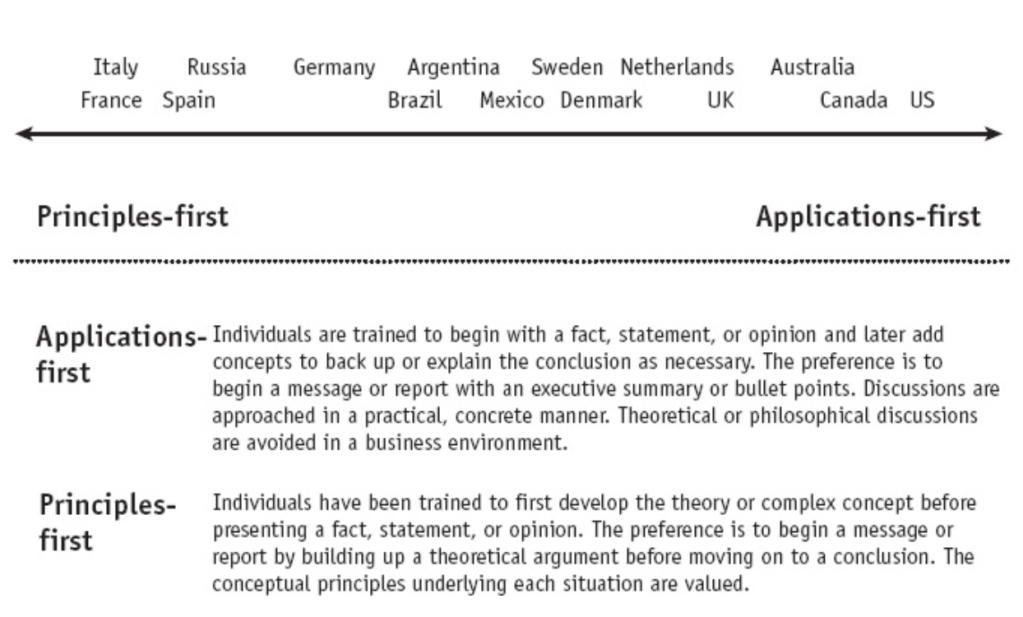

- Persuading: principles-first vs applications-first

- Leading: egalitarian vs hierarchical

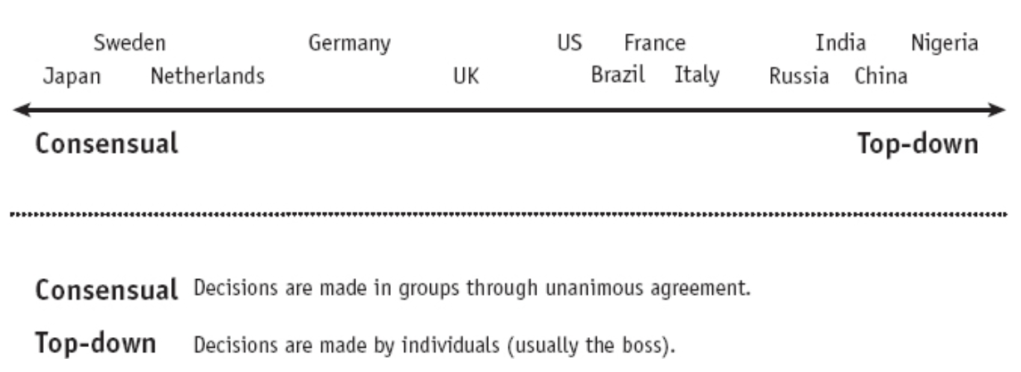

- Deciding: consensual vs top-down

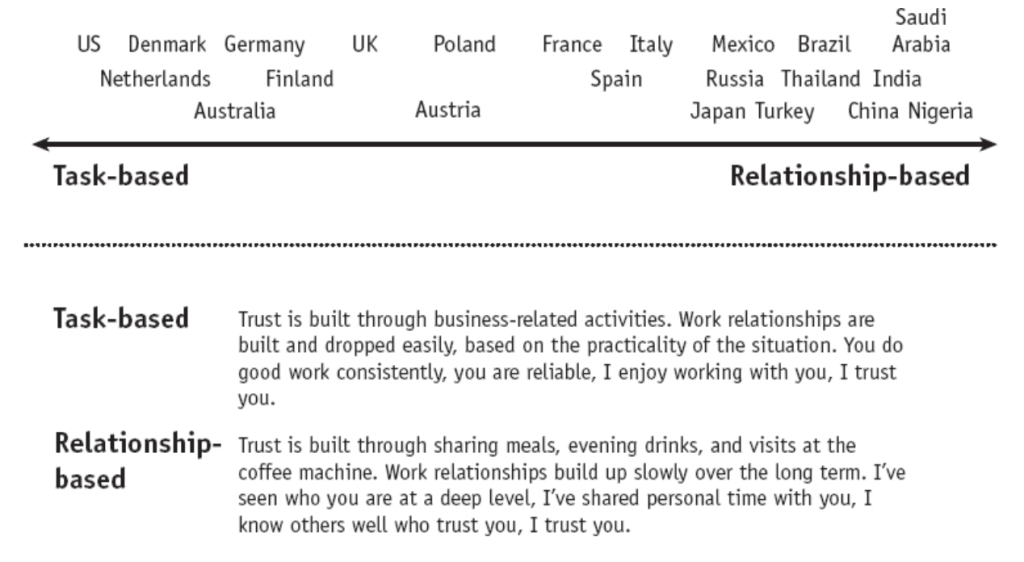

- Trusting: task-based vs relationship-based

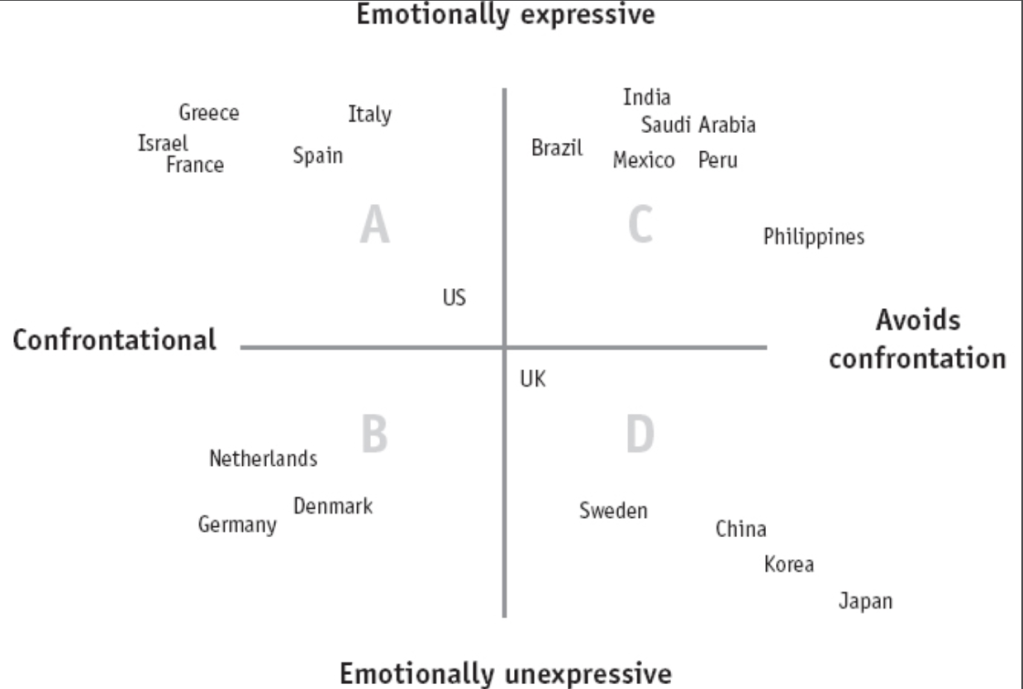

- Disagreeing: confrontational vs avoids confrontation

- Scheduling: linear-time vs flexible-time

The culture sets a range, and within that range, each individual makes a choice. It is not a question of culture or personality but of culture and personality.

If we compare two cultures on the 8 axes we may find that portions of their ranges overlap, while other portions do not. So a concept relevant in understanding the meaning of the 8 scales is the concept of cultural relativity. The idea is that when analyzing how people from different cultures relate to one another, what matters is not the absolute position of either culture on the scale but rather the relative position of the two cultures.

“When you are in and of a culture – as fish are in and of water – it is often difficult or even impossible to see that culture. Often people who have spent their lives living in one culture see only regional and individual differences…When interacting with someone from another culture, try to watch more, listen more, and speak less. Listen before you speak and learn before you act.

1️⃣ Listening to the Air – Communicating Across Cultures

“Good communication is about clarity and explicitness, and accountability for accurate transmission of the message is placed firmly on the communicator: ‘If you don’t understand, it’s my fault.’” But other than being a good communicator is essential to be also a good listener.

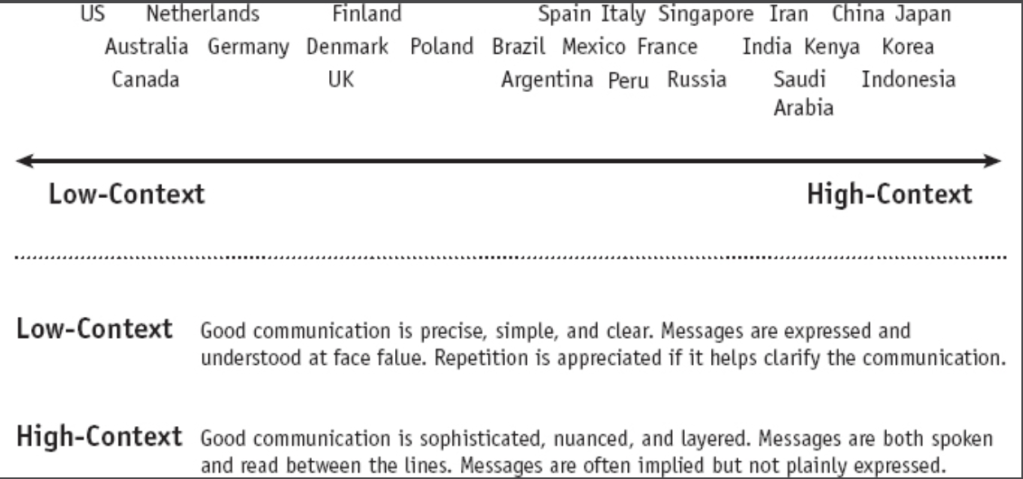

Low-context vs high-context

- low-context communication: people from these cultures are conditioned from childhood to assume a low level of shared context. Effective communication must be simple, clear, and explicit to effectively pass the message, and most communicators will respect this requirement, usually without being fully conscious of it. “Tell them what you will tell them, then tell them, then tell them what you have told them.”

- high-context communication: this communication style depends on unconscious assumptions about common reference points and shared knowledge.

If we are from a low-context culture we may perceive a high-context communicator as secretive, lacking transparency, or unable to communicate effectively. On the other hand, if we are from a high-context culture we might perceive a low-context communicator as inappropriately stating the obvious or even condescending and patronizing.

A relevant observation is that education tends to move individuals toward a more extreme version of the dominant cultural tendency.

Strategies for working with people from higher-context cultures:

- practice listening more carefully → reflecting more, asking more clarifying questions, and being more receptive to body language cues (”read the air”)

- ask open-ended questions and if something is not clear simply asking for clarification can work wonders

Strategies for working with people from lower-context cultures:

- be as transparent, clear, and specific as possible

- assert your opinions transparently

- if you are not sure that your message got absorbed, feel free to ask

Multicultural teams need low-context processes.

“The tendency to put everything in writing, which is a mark of professionalism and transparency in a low-context culture, may suggest to high-context colleagues that you don’t trust them to follow through on their verbal commitments.”

2️⃣ The Many Faces of Polite – Evaluating Performance and Providing Negative Feedback

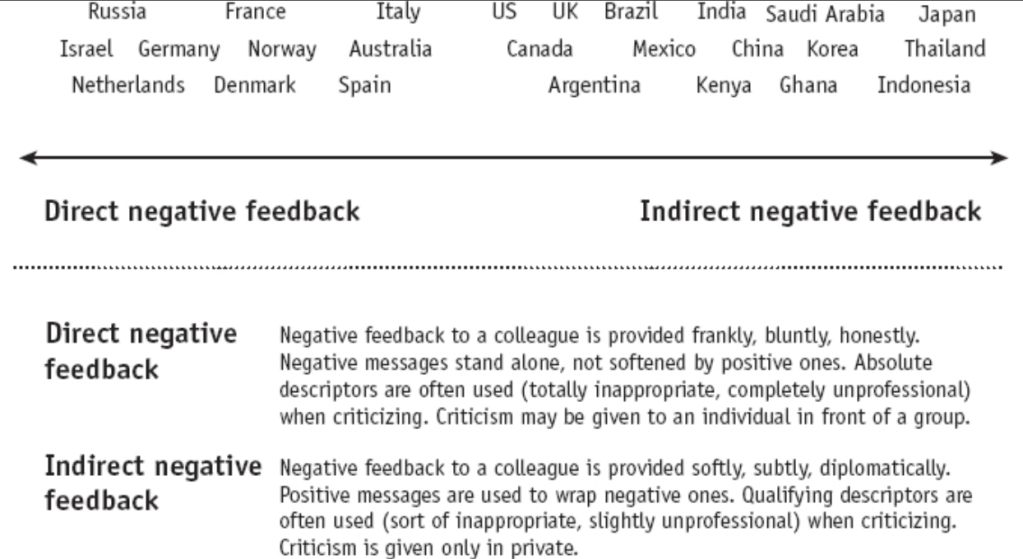

Offering negative feedback (also known as constructive feedback) is a powerful tool that could motivate your team or it can demoralize it. So it should be used carefully. The Evaluating scale will provide us with important insights into how to give effective performance appraisals and negative feedback in different parts of the world.

A simple way to identify how a culture handles negative feedback is by listening carefully to the types of words people use:

- more direct cultures tend to use upgraders, words that make the negative feedback feel stronger like “absolutely”, “totally”, “strongly” – “This is absolutely inappropriate”, “This is totally unprofessional”.

- more indirect cultures use more downgraders, words that soften the criticism, such as “kind of”, “sort of”, “a little”, “a bit”, “maybe”, “slightly” – “We are not quite there yet”, “This is just my opinion”

A very insightful sample of what is said and actually it means:

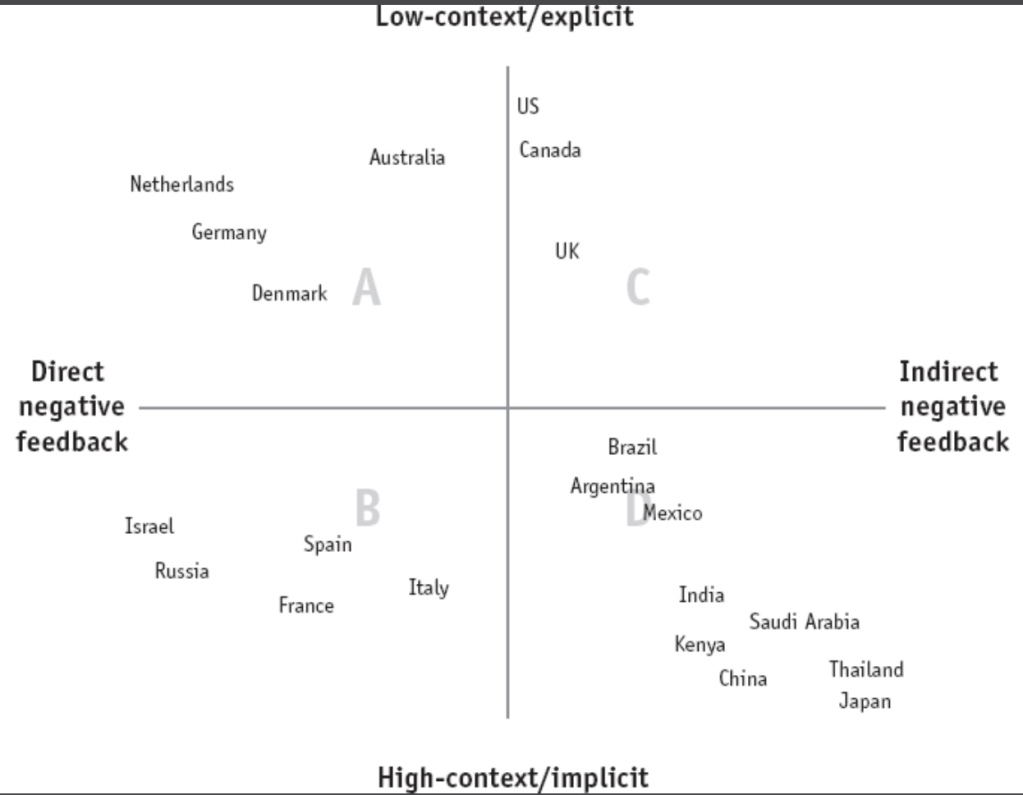

Mapping the Communicating scale against the Evaluating scale gives us 4 quadrants (see the image below):

- low-context and direct with negative feedback: these cultures are perceived as direct so it makes communication from people in this quadrant fairly easy to decode – their messages are not intended to be offensive but rather as a simple sign of honesty, transparency, and respect for your own professionalism. One rule for working with cultures that are more direct than yours on the Evaluating scale: “Don’t try to do it like them” – if you try to do it like them you run the risk of getting it wrong, going too far, and making unintended enemies – accept their criticism positively because it is not meant to offend you.

- low-context and indirect with negative feedback: 1) when providing an evaluation, be explicit, genuine, and low-context with both positive and negative feedback; 2) try, over time, to be balanced in the amount of positive and negative feedback you give; 3) frame your behavior in cultural terms – explain your communication style.

- high-context and direct with negative feedback: these are the cultures that have finessed the ability to speak and listen between the lines, but they give negative feedback that is sharp and direct.

- high-context and indirect with negative feedback: negative feedback is generally soft, subtle, and implicit; any negative feedback should be given in private, regardless of how much humor or good-natural ribbing you wrap around it. Make a message blurry – give the feedback slowly, over some time, so that it gradually sinks in.

3️⃣ Why Versus How – The Art of Persuasion in a Multicultural World

“The art of persuasion is one of the most crucial business skills. Without the ability to persuade others to support your ideas, you won’t be able to attract the support you need to turn those ideas into realities.”

Our ability to persuade others depends not simply on the strength of our message but on how we build our arguments and the persuasive techniques we employ.

Principles-First vs Applications-First

Principles-first reasoning (or deductive reasoning) derives conclusions or facts from general principles or concepts → we start with the general principle and move from it to a practical conclusion. These cultures prefer to understand the basis of the framework before they move to the application.

Applications-first reasoning (or inductive reasoning) – the general conclusions are reached based on a pattern of factual observations from the real world → we observe data from the real world. Based on these empirical observations, you draw broader conclusions. These cultures like to receive practical samples upfront.

“Take math class as an example. In a course using the applications-first formula, you first learn the formula and practice applying it. After seeing how this formula leads to the right answer again and again, you then move on to understand the concept or principle underpinning it. This means you may spend 80% of your time focusing on the concrete tool and how to apply it and only 20% of your time considering its conceptual or theoretical explanation…By contrast, in a principles-first math class, you first prove the general principle, and only then use it to develop a concrete formula that can be applied to various problems.”

In business, people from principles-first cultures generally want to understand the WHY behind a request, or decision, meanwhile the applications-first are more focused on the HOW.

When your audience or your team is coming from both areas, you should balance between these 2 styles:

- build team awareness by explaining the scale.

- a cultural bridge can help a lot – if you have a person who is bicultural or has experience interacting with multiple cultures, involve that person to facilitate the interactions

- understand and adapt to one another’s behaviors

- patience and flexibility are key because cross-cultural effectiveness takes time

4️⃣ How Much Respect Do You Want? – Leadership, Hierarchy, and Power

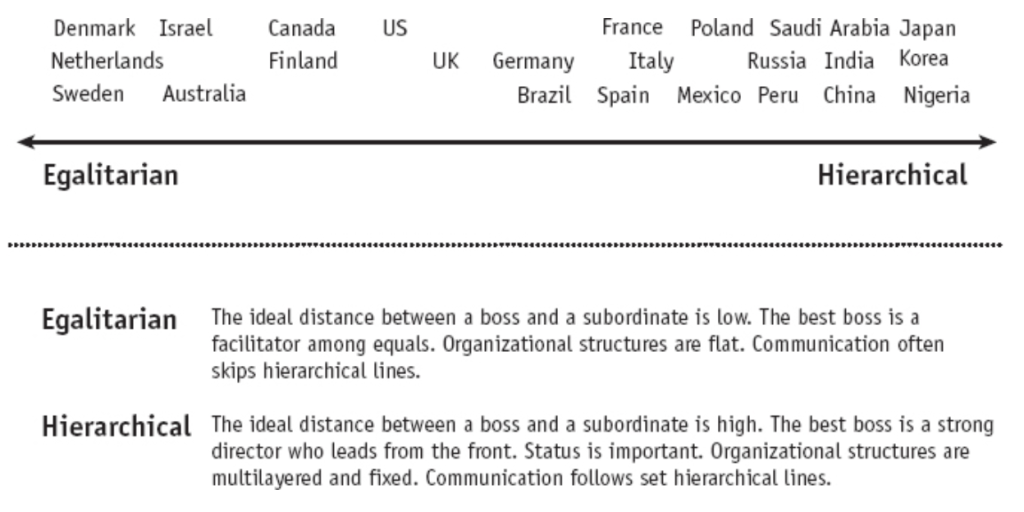

Hofstede was the first person to use significant research data to map world cultures on scales. He developed the term “power distance” and defined it as “the extent to which the less powerful members of organizations accept and expect that power is distributed unequally”. Power distance relates to questions like:

- How much respect or deference is shown to an authority figure?

- How god-like is the boss?

- Is it acceptable to skip layers in your company? If you want to communicate a message to someone two levels above or below you, should you go through the hierarchical chain?

- When you are the boss, what gives you an aura of authority?

Low power distance means egalitarian, and high power distance means hierarchical.

If you are working with people from a hierarchical society:

- Communicate with the person at your level. If you are the manager, go through the manager with equivalent status, or get explicit permission to hop from one level to another.

- If you do email someone at a lower hierarchical level than your own, copy the manager.

- If you need to approach your manager’s manager or your subordinate’s subordinate, get permission from the person at the level in between first.

- When emailing, address the recipient by their last name unless they have indicated otherwise – for example, by signing their email to you with their first name only.

If you are working with people from an egalitarian society:

- Go directly to the source. No need to bother the boss.

- Think twice before copying the boss. Doing so could suggest to the recipient that you don’t trust them or are trying to get them in trouble.

- Skipping hierarchical levels probably won’t be a problem.

If you want to make decisions and get input from your team that respects your authority so much that you are unable to get the input you need then you should (hierarchical culture):

- Ask your team to meet without you to brainstorm as a group and then to report the group’s ideas back to you.

- When you call a meeting, give clear instructions a few days before about how you would like the meeting to work and what questions you plan to ask.

- If you are the manager, remember that your role is to chair the meeting. Don’t expect people to jump in randomly without an invitation. Invite people to speak up.

For a team from a culture that is more egalitarian than your own:

- Introduce management by objectives, starting by speaking with each employee about the visions for the coming year and inviting them to bring their own objectives and ideas. Involve them in the process.

- Make sure the objectives are concrete and specific and consider linking them to bonuses or other rewards.

- Set objectives for 12 months and check them periodically – maybe once a month based on the progress decide if you give them more space for self-management or you can get more involved.

5️⃣ Big D or Little D – Who Decides, and How?

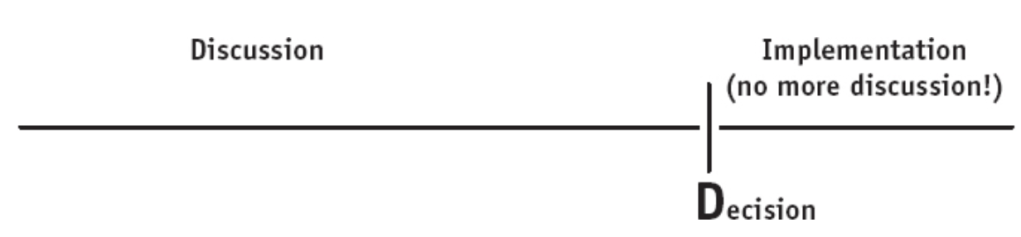

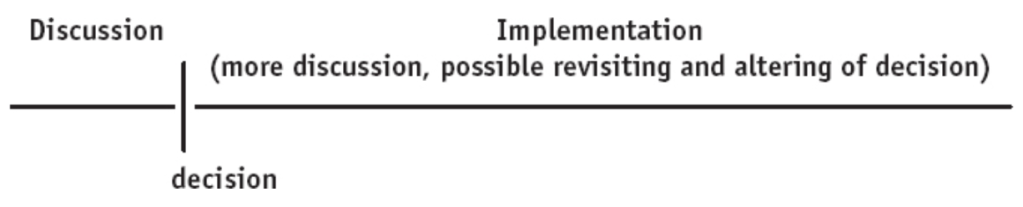

There are 2 different styles of decision-making:

- in a consensual culture, the decision-making may take quite a long time, since everyone is consulted, but once the decision has been made, the implementation is quite rapid, since everyone is involved in the process and they know in detail all the aspects → This is called a decision with capital D

- in a top-down culture, the decision-making is done by an individual. The decisions are made quickly, early in the process, by one person. But each decision is also flexible, a decision with lowercase d. As new info appears, the decisions could be revisited or altered, so the plans are in continuous change it means that implementation can take a long time.

If you are part of a team that prefers a more consensual decision-making process, try to apply the following ideas:

- expect the decision-making process to take longer and to involve more meetings and extensive communication via different channels

- do your best to demonstrate patience and commitment throughout the process

- check in with your counterparts regularly to show your commitment and be available to answer questions

- cultivate informal contacts within the team to help you monitor where the group is in the decision-making process

- resist the temptation to push for a quick decision, instead focus on the quality of the info gathered

If you are working with a group of people who favor a more top-down approach to decision-making, try to apply the following ideas:

- expect decisions to be made by the manager with less discussion and less soliciting of options than you are accustomed to. The decision may be made before, during, or after a meeting, depending on the org culture

- be ready to follow a decision even if your input was not solicited or was overruled

- when you are in charge, solicit input and listen carefully to different viewpoints, but strive to make decisions quickly

- when the group is divided about how to move forward and no obvious leader is present, suggest a vote

- remain flexible throughout the process because the decisions are rarely set in stone

6️⃣ The Head or the Heart – Two Types of Trust and How They Grow

Trust is a critical element of business in every country in the world. The type of trust you feel for one person is very different from the type of trust you feel for another. One simple distinction is between two forms of trust: cognitive trust and affective trust.

Cognitive trust is based on the confidence you feel in another person’s accomplishments, skills, and reliability. This is trust that comes from the head.

Affective trust is based on feelings of emotional closeness, empathy, or friendship. This type of trust comes from the heart.

The scale used to evaluate this dimension of trust has 2 extremes: task-based and relationship-based cultures. In task-based cultures, “business is business”, in the cultures that are relationship-based “business is personal”.

Peach 🍑 vs Coconut 🥥 models of personal interaction

- 🍑 in peach cultures (US or Brazil), people tend to be friendly (”soft”) with others they have just met. They smile frequently at strangers, move quickly to first-name usage, share info about themselves, and ask personal questions of those they hardly know. But after a little friendly interaction with a peach person, you may suddenly get to the hard shell of the pit where the peach protects his real self. In these cultures, friendliness does not equal friendship.

- 🥥 in coconut cultures (Poland, France, Germany, Russia) people are more distant (like the tough shell of a coconut) from the people they don’t have a friendship with. It takes a while to get through the initial hard shell, but as you do, people will become gradually warmer and friendlier. While relationships are built up slowly, they do tend to last longer.

One productive way to start putting trust deposits in the bank is by building on common interests. You need to be intentional and make the effort to find similarities between you and the other person. Investing time in establishing trust will often save time and many other resources in the long run because, in many cultures, the relationship is your contract. You can’t have one without the other.

Sharing meals is a meaningful tool for trust-building in nearly all cultures. But in some cultures, sharing drinks, particularly alcoholic drinks is equally important

If you are working with people from a task-based culture, for communication use the most efficient medium – everything is accepted as long the message is communicated clearly.

But when working with people from a relationship-based culture, begin by choosing a communication medium that is as relationship-based as possible (face-to-face meeting preferably).

When in doubt, the best strategy may be to simply let the other person lead.

Trust is like insurance – it is an investment you need to make upfront before the need arises.

7️⃣ The Needle, Not the Knife – Disagreeing Productively

To assess where your own culture falls on the Disagreeing scale, the question that should be asked is “If someone in my culture disagrees strongly with my idea, does that suggest they disapprove of me or just of the idea?”. In more confrontational cultures, it is normal to attack someone’s opinion without attacking that person. In avoid-confrontation societies, these two things are tightly interconnected.

Emotional expressiveness is not the same thing as comfort in expressing open disagreement.

Quadrants A – emotions pour out, including the ones associated with disagreement, which can be expressed with little likelihood of relationships being harmed.

Quadrant D – emotions are expressed more subtly and disagreements are expressed more softly.

Quadrant B – cultures that are not emotionally expressive, but they see debate and disagreement as a critical step on the path to truth.

Quadrant C – the people who speak with passion, but they are very sensitive. For them, it is not easy to separate the opinion from the person. They take it personally.

How to get global teams to disagree agreeably, especially when your team is in quadrant C or D:

- if you are the manager, offer your opinion at the end, after all of them talked

- separate the ideas from the people proposing them (make a brainstorming, with anonymous ideas)

- conduct meetings before the meeting

- adjust your language, avoid upgraders, and employ downgraders

- you could mention that you play the devil’s advocate so you can explore both sides

Sometimes just a few words of explanation framing your behavior can make all the difference in how your actions are perceived.

8️⃣ How Late Is Late? – Scheduling and Cross-Cultural Perceptions of Time

The Scheduling scale is affected by several historical factors that shape the ways people live, work, think, and interact with one another.

The cultures where the relationships are a priority will be put before the clock so a big part of them are under the flexible-time side of the scale.

Learn what works best in that culture and do things the way they do them. However, understanding the cultural nuances and gauging them precisely can sometimes be challenging. Also, sometimes it helps a lot if the leader establishes a clear and explicit team culture or lets the team decide on a guideline that should be respected by everyone.

“The way we are conditioned to see the world in our own culture seems so completely obvious and commonplace that it is difficult to imagine that another culture might do things differently. Only when you start to identify what is typical in your culture, but different from others, can you begin to open a dialogue of sharing, learning, and ultimately understanding.”

🤓 If you want to learn more…